We cross a small yellow dirt road and suddenly everything disappears. A green wall about two metres high, very dense, creates a kind of tunnel on both sides. All around us is sugar cane. During Gems Joacin’s funeral, the melody of the wind in the cane fields seemed gentle to me, but now I feel it is a more melancholic music, like something from another time.

Pastor Wilson tells me that if you were to «sail» across this kind of green sea, it would be possible to cross the 200 kilometres or so that separate Punta Cana from Santo Domingo.

It is our penultimate meeting and we set off in the morning with the promise of finding Mikelson. I’m surprised we’re looking for him here, because one of the few clear things in the blurry video that has obsessed me for almost a month is that the policeman throws Mikelson off a rooftop in an urban neighbourhood. But I don’t say anything to the pastor. I think my guide wants to show me something else, the source of all the ills of the Haitian community, which has to do with sweetening the world for others.

View of sugarcane plantations near Punta Cana.

In 2024, sugar cane is still cut and processed with machetes and muscle power, as it was in colonial times, when the French and Spanish ruled the island. Sugar cane is still one of the economic activities that requires the most Haitian labour in the Dominican Republic.

During the colonial era, slaves lived in bateyes, ghettos of shacks where they never mixed with Dominicans (batey is a word from the Taíno language, which referred to a ball game, but when the Europeans exterminated these indigenous people, it came to refer to these homes of agricultural workers). The plantations passed from the hands of the colonists to the Dominican State, and then the large transnational companies arrived, such as Central La Romana, the largest of all, owned by the Fanjul brothers, a family of Cuban origin that has created a sugar empire from Florida. The conditions for Haitians, however, have changed little.

In September 2022, the US government, through the Customs and Border Protection (CBP) agency, issued a detention order to prevent all ships carrying sugar or sugar derivatives from Central La Romana from entering the country. Investigations by various international entities found five of the 11 indicators established by the International Labour Organisation to determine that conditions in a place are unacceptable and abusive for workers. Central La Romana denied the accusations of the US investigators, who detected everything from child labour to forced labour in their investigation, modern words to describe something very similar to that great curse of the Haitian people: slavery.

We arrived at Batey la Romanita, a kind of island of trees that breaks the monotony of the green sea. A group of children were playing football on a piece of land.

«Look, Juan, there’s Real Madrid,» Pastor Wilson said to me, laughing loudly.

The batey is in a state of lethargy. Several men squatting on the ground stare at us, and some women emerge from the 14 faded barracks. An old man waves us over, speaking softly in a mixture of Spanish and French.

He tells us, his mouth moving as if chewing, that after 53 years of working in the batey, he has not been paid his pension. Officially, cane workers earn 15,000 pesos a month, equivalent to 283 US dollars.

However, there is not enough work all year round and they are often paid according to the weight of the cane they cut. With this pay, it is very difficult to save for old age. Without a pension, these people are at the mercy of the batey and its inhabitants, and at the mercy of the company and apartheid.

In the La Romita batey, the elderly complain that they have no right to retirement or severance pay after decades of working on the sugarcane plantations.

A group of elderly people vegetating in the shade of an old barracks tell me that Central La Romana fired them. A very old woman asks me for some money for food and shows me with a pitiful smile that she lost her teeth some time ago. Another woman begs Pastor Wilson for help. She tells him that her husband died after working for more than 40 years in the cane fields. She says that company representatives have visited her and told her that she may have to leave, as the house she has lived in all her life may be needed for new workers.

The scene has a ghostly air, but everything indicates that I won’t find Mikelson here, the ghost I’ve been looking for for a month. Suddenly, I see a kind of apparition.

A brand-new bus speeds down the street in front of the batey, leaving a trail of yellow dust behind it. When I ask the Haitians who is on the bus and where they are going or where they are coming from, they seem to have forgotten their Spanish. In Creole, they tell Pastor Wilson that they are Americans.

I ask him to insist, and he only manages to get two words out of them, «Americans» and «voodoo.»

***

Detail of the house of a boko, a voodoo priest, in Santo Domingo. Voodoo has been a religion of identity and resistance for Haitians throughout history.

One night in August 1791, as a thunderstorm raged in the sky, a mambo or voodoo priestess named Fatiman called out to the African loas above and to the guede, the ancestral dead, below. The hands of black men and women beat drums like thunder in a place near Cap Francais, now Cap-Haïtien, on the French side of Hispaniola. It was on that night that the slave system began to die.

Hundreds of black slaves fled the plantations and gathered in a remote place in the mountains, a place where the now-extinct Taínos, murdered by the Spanish and the plagues they brought with them, worshipped the gods who died with them. The place was called Bwa Kayiman, or Bois Caimán, which could be translated as «forest of the caimans».

The ceremony was led by Mambo Fatiman and Dutty Bokman, one of the heroes of Haitian independence. A freed slave who had arrived from Jamaica and, steeped in French ideas of liberty and equality among people, soon led this large, angry mass of kidnapped Africans and their descendants.

That night, Mambo Fatiman sacrificed a black pig and those present drank its blood and swore to destroy the white masters. Historical tradition says that the loascame down from a large tree. Papa Legba opened the pantheon and then Shango, Debehlla, Achun came down, as well as Ogun, the lord of war and iron, and Loko, the lord of the forests and trees. The loaswere accompanied by an army of guedes, the dead ancestors. That crowd, feeling the power of those offended gods who had travelled with them from Africa on European ships, threw themselves with machetes and daggers in hand onto the sugar cane plantations.

Not all the slaves came from the same places, nor did they speak the same languages, but their ritual practices were similar and their gods referred to the same religious universe. Thus they understood each other. To the beat of the drum. On that night in August 1791, in one of the Greater Antilles of the Caribbean, thousands of slaves put to the sword those who had stolen their freedom, those who had tried to turn them into animals.

***

Rusty trucks in a sugarcane plantation batey near Punta Cana.

I return to the sugar cane plantations to unravel the mystery of the white bus. This time I travel alone. The endless green sea and the shells of old trucks play with my mind and I feel as if I have travelled back in time, to an ethereal, desolate past.

I ask about the Americans and voodoo, the two words that were mentioned to Pastor Wilson the other day. I ask with confidence, as if I know what I’m talking about, even though I have no idea.

The answers lead me to the back of a new batey. I come across an old cockfighting ring that looks abandoned, where four near-skeletal children are now playfighting. There are a few wooden houses with dilapidated tin roofs. Several young men approach me. I say the same two words to them, and one looks at a watch on his wrist.

«Almost, they’ll be here at three,» one of them tells me, pointing to one of the wooden shacks painted red and black. I knock on the door and an old man appears. Inside there are ritual drums, candles, cans of baby powder, machetes and bottles of liquor. It is a voodoo altar, or so it seems.

The old man tells me I have to wait for the owner. While we wait, a small group of curious people gather to get a closer look at the stranger who has arrived asking questions. They tell me that leaving the batey is very dangerous now that the deportations have intensified. Several people have gone out to buy food and never returned.

I ask them about their daily food, and they tell me that the diet in the batey is limited to cassava, rice and plantains. Never all three together. I ask an elderly woman if they eat this monotonous diet three times a day, and she looks at me with a mixture of indignation and anger.

«Three times a day? We eat once a day!»

At that moment, a van appears. It looks as out of place as a refrigerator in a desert. Margarita the witch gets out and introduces herself. She is a small Dominican woman of about 50. At first she is hostile, but she calms down when I tell her I am a journalist interested in voodoo. After a chat and some suspicious questions, she invites me into the red and black room.

Margarita tells me that this house is hers and that she organises a voodoo show for foreign tourists every day. She tells me that she charges 150 dollars a day to organise the show and that she gives a few pesos to a group of bateyanos to play drums and put on the show.

She tells me that the real business isn’t hers; she’s subcontracted by a German named Norbert. He organises tours for Europeans and North Americans. He takes them to beaches, restaurants and a river. At three o’clock in the afternoon, he brings them here with the promise that he will show them something unique, rarely seen by white people: an authentic voodoo ritual taking place that very day.

Shortly before that time, a jeep appears. It is Margarita’s daughter, a beautiful brunette with full lips, dressed in jeans and a belly-baring top. She has very eye-catching tattoos on her hips and neck.

We talk about the outfits she will wear in the show. She tells me that she chooses them herself, according to her own criteria. Her mother scolds her and tells her to change quickly because the tourists are about to arrive. She returns in costume, looking like a mishmash of symbols with a handful of necklaces, bracelets and scarves. Her mother lights candles and sets up chairs.

Three elderly Bateyan men take their places in front of large drums, and one of them dresses up as Bokó, in the same style as the girl.

«Let’s say you’re my nephew because Norbert is going to ask me. Remember, this is his business,» says the witch, placing me next to her, behind the men and the drums.

At the house of «Witch Margarita», preparations are underway for the voodoo ceremony that will be held for tourists.

The white bus arrives on time. There are about 50 tourists. They are all white and dressed for the beach. Norbert is a man in his 70s. He is bald and dressed in a red shirt, brown shorts and beach sandals.

The five men begin to beat the drums to set the mood and the tourists sit down on the benches, taking photos and videos of the scene. The officiants are five bateyanos. Three are elderly men who were dismissed by the sugar cane company without compensation, and the others are young, burly men who beat a monotonous rhythm on the drums.

Norbert begins to explain in German and French, and the tourists nod and open their mouths in surprise. He directs the event as if he were a bokó himself and snatches a pair of maracas from an elderly man’s hands and plays them for his customers.

In the middle, a fire burns and Margarita’s daughter moves in a chaotic dance, as if in a trance, pretending to be mounted by a loa. Norbert invites the tourists to play the drums and maracas themselves. Then those white people, still with sand in their sandals, dance without any sense of rhythm, dancing and playing the drums.

As I watch the scene, I remember the bokó Winston Pierre, the voodoo priest who gave me a master class in Haitian history and who patiently explained to me the «biographies» of a dozen African loas. He wouldn’t even let me take pictures of his fetishes for fear of offending those loas. I also remember the more than ten bokós and ungans that Moisés, my first guide on the Haitian underground railway, took me to visit. They bring their fetishes from Haiti in coffins, hidden from the Dominican police among merchandise, and they do not allow even their own relatives to approach them.

At that time, at the beginning of this investigation, I hoped that this part of the railway, perhaps the most hidden of all, would lead me to Mikelson. Voodoo, like many religions of African origin, has been a practice of resistance, a way of bringing their home with them wherever they went, and a way of being strong in something that chains cannot capture, and it continues to be so in this new apartheid. According to the Constitution of the Dominican Republic, there is freedom of worship, but in practice the state persecutes voodoo as part of its persecution of everything Haitian.

«Police dismantle shack used by Haitian nationals for witchcraft and sorcery in Cabarete, Puerto Plata,» the official website of the national police reported on September 12, 2023. According to the same publication, «the witch doctor» Papallo kept the neighbourhood’s inhabitants in a constant state of anxiety with his rituals.

In March of this year, the police uploaded a video to Instagram and X showing them dismantling an altar. The person recording the video is shocked when he pulls out two coffins used for ritual purposes.

«This looks like a cemetery,» he says.

After destroying the hut and taking everything out onto the street, the officers set it on fire.

«We’re not setting fire to the house because the witch doctor’s children are inside,» says one of the police officers, while in the background a group of black children watch fearfully as their father’s sacred belongings burn.

According to Simón Rodríguez, a Venezuelan journalist based in the Dominican Republic, persecuting Haitian voodoo is one of the pillars of Dominican identity and another way of creating distance between «us and them.»

During the Trujillo dictatorship, a law was passed that expressly prohibited the practice of voodoo in Dominican territory. This law — although freedom of worship is enshrined in the constitution — remains in force, and attempts to repeal it have been met with opposition from both the evangelical community and various political factions.

After an hour of suffocating heat, the exhausted elders of the batey stop playing their drums and the cheerful European holidaymakers finally stop the frenetic, rhythmless movements that they call dancing.

Tourists dance during a voodoo ceremony that a German businessman has organized for them.

For a moment, I feel like speaking up and telling them how lucky they are that these people need their pennies so badly, telling them that 233 years ago, on this very island, thousands of people like these old folks hacked people very much like themselves to pieces. I would like to tell them that the reasons are similar: they wanted to kill their culture and their freedom. Those with whips and chains; these with money.

But I don’t. I rush out to my truck. The mystery of the white bus is solved: everything seems to indicate that the problem isn’t voodoo, but rather who practises it, who dances it.

I’m here looking for something else.

***

It’s the morning of October 26, 2024 and Pastor Wilson drives his lopsided truck. He seems cheerful, even though every day this man has to deal with complaints and calls for help from the Haitian population in this beautiful corner of the island. I’ve only been working on this investigation for a little over a month, and I already feel the overwhelming weight of dozens of messages and calls from desperate people. They call to tell me about some horror, asking for help that is often impossible to give them. They send terrible videos showing black men and women lying on the ground, being beaten, caged or screaming in rage in the chilling Haina Holiday Resort. Always suffering, always losing. These videos and complaints will continue to arrive on my phone even after I leave this island, each time more graphic than the last.

Pastor Wilson himself will be arrested by the police in two day times. A group of uniformed men will arrive at his home at 11 pm on 28 October and take him away in handcuffs in front of his children. He will spend the night in uncertainty in a cell and will be released in the morning because, as he will later say, he was accused of an unspecified fraud.

On the day of his release, he will receive death threats and consider fleeing Punta Cana. He will not do so, however, as the underground railway that protects Haitians as best it can must continue to operate, always in the shadows, always losing everything, always gaining very little.

This is my last day reporting in the Dominican Republic, and I have given up trying to persuade the pastor to take me to Mikelson, the man thrown from a rooftop by a police officer. His tragedy came to me in the form of a video a few days before I arrived in this country.

It became an obsession. I thought it would be as scandalous as the video showing Rodney King being almost killed, or the one showing a police officer suffocating George Floyd. «I can’t breathe,» he said.

Los Angeles burned for Rodney King in 1992, and the United States trembled for Floyd in 2020. Not for Mikelson. There will be no streets taken over, no cars set on fire, no headlines. Perhaps, in the eyes of the world, not all people are equal. Perhaps my obsession with finding this man will prove futile in a country where hundreds of thousands are Mikelsons. I looked for a drop, then realised I was looking for it in the sea.

Today, once again, I let myself get carried away. Today Pastor Wilson is smiling, and his smile is contagious. He is happy because he managed to get a hospital to give him a back brace for a man with broken ribs. Amidst so much tragedy, this tough man has learned to find joy in the small victories of those who always lose: saving a girl from death after her mother was deported, getting medicine to cure an infected caesarean section, getting a place in the hospital for a man who was skinned alive, managing to bury a man who was murdered in a cemetery.

Along the way, he tells me that he doesn’t understand why his people are so hated in this country, given that they are the ones who have historically produced its wealth, whether in the sugar cane fields, the coffee plantations, the tobacco fields, the textile factories or building hotels in Punta Cana.

Several days ago, while we were searching for Gems Joacin’s body in the Matamosquito neighbourhood, one of his collaborators told me, «It’s as if we had raised a lion cub, giving it the best milk, and now it’s coming after us to eat us.»

We entered the dirt alleys of a neighbourhood near Matamosquitos. In one of the wooden and tin houses on the side, the man who Pastor Wilson had brought the orthopaedic brace for was waiting for us.

«Juan, meet Mikelson!» he says enthusiastically as he puts his thick hand on the boy’s shoulder.

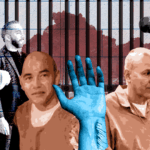

Mikelson, the 19-year-old Haitian man who was thrown off a rooftop by a police officer. In the video, he explains what happened that morning.

Mikelson has a frightened expression, but still retains that sparkle in his eyes that children have. He is only 19 years old. In one hand, he holds the same vest he was wearing when, in early October 2024, Dominican police officers threw him off a rooftop. He does not speak Spanish, so Pastor Wilson has to translate.

That day, Mikelson was getting ready to go to a hotel construction site in the tourist area of Punta Cana and had already put on his reflective vest when he heard screams. Several trucks were hunting down Haitians in the neighbourhood. He heard them kicking down the door of his tin room.

The entire room shook, and he opened a wooden window next to his bed to escape. He climbed out, alongside other Haitians, and they began to climb. They managed to get onto the roof, but behind them a policeman also climbed up.

«Catch him, catch him!» Mikelson remembers the officers shouting from below.

The policeman caught his neighbour, who managed to slip out of his hands and jump onto another roof. Mikelson couldn’t make it; he was trapped between the edge of the roof and the policeman.

«Throw him down, throw the Haitian down!» shouted the policemen below, so the uniformed officer grabbed him by the neck and belt and threw him down.

While this was happening, a woman recorded everything while crying and shouting, «Baba, baba, they killed him!»

What she didn’t record was that between the roof and the ground there was a tangle of loose electrical cables. Mikelson fell onto them, slowing his fall. Then came the impact with the ground. He was unconscious. The police left him there and drove away.

His neighbours picked him up, washed his face and immobilised his back. They contacted a pastor named Wilson, and he managed to get him to a hospital and save his life. The woman in the video passed it on to an acquaintance, who passed it on to another, and so on until it reached the eyes of the writer of this article.

Mikelson was born in a village near the Artibonito River in southern Haiti. He came alone, without his family and without knowing anyone, to work in this country a year ago. Other compatriots told him that in the Punta Cana area, Dominicans hire Haitians regardless of their immigration status. Mikelson came, like thousands of other Mikelsons, to work in the Dominican Republic while the police hunt them down.

Mikelson walks bent over, with several broken ribs and a host of less serious but equally painful injuries. From now on, it will be even more difficult for him to build hotels in this southern part of the island of Hispaniola, where the last system of racial segregation in the Antilles tightens its grip on a poor and desperate population. The policeman who threw him off a roof destroyed the only tool he has in life: his body. The screws are still tightening. The train keeps rolling. Mikelson sleeps every night with the window open.

Pastor Wilson and Mikelson in Punta Cana.

The End.

* This investigation is a production of Redacción Regional and Dromómanos and was originally published in December 2024 thanks to the support of the Consortium for Supporting Regional Journalism in Latin America (CAPIR), led by the Institute for War and Peace Reporting (IWPR).